Warning: mentions suicide, may trigger existential crisis. Straussian.

There is but one truly serious philosophical problem and that is suicide.

- Albert Camus

If you’re an antinatalist, you should kill yourself.

If you think most of contemporary academic philosophy is trivial, obscure semantics, here’s a scholar who doesn’t shy away from the Big Questions — David Benatar argues in his book Better Never to Have Been:

- Coming into existence is always a serious harm

- It is always wrong to have children

- It is wrong not to abort foetuses at the earlier stages of gestation

- It would be better if, as a result of there being no new people, humanity became extinct

Benatar was profiled by the New Yorker and appeared on Sam Harris’ podcast. Anecdotally, antinatalist sentiments are on the rise, but if you look closer none of the arguments hold water.

- Universal A Priori Antinatalism

- Negative Utilitarianism

- Universal A Posteriori Antinatalism

- To Be Or Not To Be, That Is The Question

Universal A Priori Antinatalism

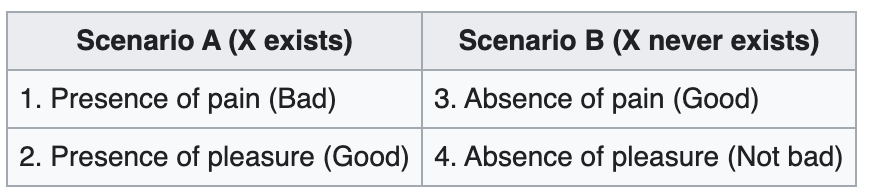

I’ll try to steelman Benatar’s Asymmetry argument, which goes:

He thinks that coming into existence entails pain and pleasure, while not coming into existence entails neither pain nor pleasure; since the absence of pain is good, and the absence of pleasure is not bad, not coming into existence is ethical.

As José at Nintil notes, Benetar’s sleight-of-hand is in asserting that the absence of pain is good even though there is no one to benefit from it. If the absence of pain is good, I think it follows that the absence of pleasure is bad, but Benatar asserts that the absence of pleasure is not bad. He explains the Asymmetry using four other commonly accepted asymmetries:

First, procreational duties: we have a duty to avoid bringing miserable people into existence, but no duty to bring happy people into existence. To me, this asymmetry fails because the intuition that most duties regard non-maleficence more than beneficence applies to existing people. The real asymmetry is the default of not having kids (no cost) versus pregnancy and raising the kid (high cost). If bringing into existence people with good lives was as easy as pressing a button (or very cheap artificial wombs), it would even be our duty of beneficence to do so. Benatar considers this rebuttal, and does not explain why the interest of a future person grounds a reason to avoid their potential suffering but not a reason to give them a life, and only hand waves in the direction of the next asymmetry.

Second, prospective beneficence: it is strange to justify having a child because the child would benefit, but not strange to justify not having a child because the child would suffer. As José notes, this asymmetry fails because it isn’t strange. There is no rigour behind Benatar’s assertions besides wriggling his finger and saying “that’s weird”.

Third, retrospective beneficence: we can regret having brought into existence a suffering child for the sake of the child, but cannot regret not having brought into existence a happy child. To avoid using emotional language in moral evaluations, I suggest we rephrase “regret” as “belief that it was a bad thing to have done”. This asymmetry fails because it is comparing an actuality (an existing suffering child) with a potentiality (a potentially happy child). If indeed the happy child was brought into existence, it would make sense to believe it would have been a bad idea not to have brought them into existence. With the potential child, it doesn’t exist either way — they don’t exist.

Fourth, distant suffering and absent happy people: we are sad for distant people who suffer, but not for absent happy people on uninhabited planets or islands. This asymmetry fails because it is once again comparing an actuality with a potentiality.

Negative Utilitarianism

Negative utilitarianism (NU) isn’t strictly necessary for the antinatalist argument, but antinatalists sure like to sneak it in by implication. For example, as Benatar presented to Sam Harris: would you be willing to have children who will lead hard lives if that will ensure a bright future for countless descendants after that? The implicit assumption is that an act is morally right if and only if it leads to less suffering.

As Toby Orb remarks, NU is treated as a non-starter in mainstream philosophical circles, and has never been supported by any mainstream philosopher, living or dead. This is quite an amazing lack of support: one can usually find philosophers who support any named position.

The different flavours of NU include:

- Absolute NU: only suffering counts

- Lexical NU: both suffering and happiness counts but no amount of happiness can outweigh any amount of suffering

- Lexical threshold NU: both suffering and happiness counts but there is some amount of suffering that no amount of happiness can outweigh

- Weak NU: both suffering and happiness count but suffering counts more

Absolute negative utilitarians are completely indifferent to happiness, so they would say a world devoid of happiness would just be as good as a utopia, which is absurd.

Lexical negative utilitarians are willing to sacrifice arbitrarily large amounts of happiness to avoid a pinprick, so they would prefer a world devoid of happiness and a single pinprick over a utopia with a single pinprick, which is also absurd.

Lexical threshold negative utilitarians believe in world in which n+1 people getting a pinprick is infinitely worse than n people getting a pinprick, or flipping that around a world in which there is a small quantity of moral value (the amount a pinprick takes away) that no amount of happiness can improve the world by, both of which don’t make sense because of infinity.

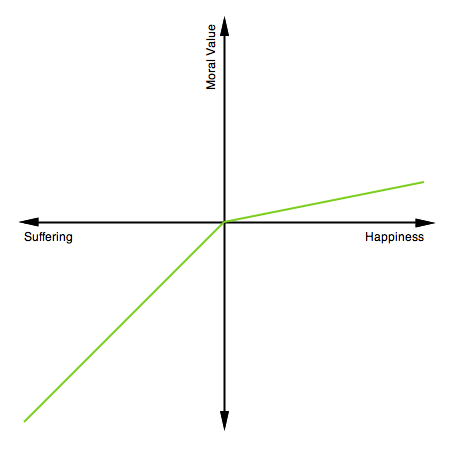

Weak negative utilitarians believe in something like:

But what is the horizontal scale supposed to represent? Negative utilitarians cannot put moral good/bad on the scale as that would be assuming a unit of happiness and suffering are equal just like classical utilitarians. They can only put “how much it contributes to an individual’s wellbeing” on the scale, which brings us to why all forms of NU are incoherent: suppose your friend pays 5 wellbeing units of suffering at the gym to gain 10 wellbeing units of happiness, weak NU says this tradeoff is immoral and you are obligated to stop your friends from going to the gym, which is absurd.

Universal A Posteriori Antinatalism

In practice, most people with NU intuitions agree that both suffering and happiness both count more or less the same:

- Strong practical NU: classical utilitarianism with the empirical belief that suffering outweighs happiness in all or most human lives

- Weak practical NU: classical utilitarianism with the empirical belief that it is more effective to focus on reducing suffering than on increasing happiness

Strong practical NU basically says that life sucks. I won’t argue against the weak practical form as I think it is reasonable and would be supported by almost all classical utilitarians.

In Every Cradle is a Grave, Sarah Perry identifies two approaches to the empirical question of whether the good parts of life outweigh the bad: preferentist (people’s preferences are good evidence for what is actually good for them) and non-preferentist.

Non-preferentists like Benatar argues that we are bad at evaluating our true quality of life, so in fact life is net negative if we can correct our biases which include:

- Pollyanna principle: we have a tendency towards optimistic view of our past, present and future

- But the claim that depressive people are more realistic in their worldview is unfounded

- Adaptation: we get used to how miserable our lives are

- Has Benatar never heard of the hedonic treadmill?

- Comparison: we judge our own wellbeing by comparing to others in relative, not absolute, terms, so we ignore the suffering experienced by everyone

- Has Benatar never heard of FOMO?

Even granting Benatar’s argument, an empirical assessment of his claims is unnecessary as these “biases” don’t invalidate our judgement; it would be like considering all perception to be wrong because optical illusions exist. Say his argument should reduce our intuition that life is worth living from 90% to 70%, the burden of proof is still up to Benatar, and he fails to make the non-preferentist case that life is not worth living.

The preferentist approach is more reliable — it is very hard to judge another person’s wellbeing, and the best judge is themselves. Antinatalist David Pearce supports a version of lexical threshold NU because of his sense of horror at Auschwitz. However, even people in such unfathomable extremes of suffering like Viktor Frankl believed that life was worth living. It’s best not to go up to Frankl and tell him “actually you were wrong you should have given up and died.”

Perry argues that the “extreme uncertainty” in predicting whether a given life would be good or not should counsel against reproduction, but in practice, every typical childless couple rely on such predictions. Perhaps they know they will be bad parents, or they find themselves in bankruptcy, or they have Huntington’s (if either parent has two disease alleles, the risk is 100%), or they know they will die before their child reaches adulthood (due to old age or cancer). As Paul Kalanithi writes in When Breath Becomes Air, he and his wife decided to have a child despite his stage IV metastatic lung cancer diagnosis. I suspect most childless couples would not think other couples who decide to bear children to be unethical. In any case, Perry relies on an incoherent strong precautionary principle that proves inadequte in asserting the core antinatalist notion that no life is worth living.

To Be Or Not To Be, That Is The Question

Benatar says we shouldn’t commit suicide because it would harm our bereaved friends and family. Well, I say he should form a suicide pact with his loved ones (he has no children of his own). Surely at some point the total suffering prevented would outweigh the suffering experienced by his third cousin twice-removed who doesn’t care about the members of the pact at all.

Taking seriously the position that life is not worth living should lead one to a philosophy of extinctionism – the stance that it would be pretty great if all humans died in their sleep tonight. Benatar tries to wriggle out of it but I say he should just bite the bullet.

To quote Epicurus’ ancient argument:

Yet much worse still is the man who says it is good not to be born, but “once born make haste to pass the gates of Death.” [Theognis, 427]

For if he says this from conviction why does he not pass away out of life? For it is open to him to do so, if he had firmly made up his mind to this. But if he speaks in jest, his words are idle among men who cannot receive them.

I grant that the fear of death is not the love of life, but to assert that no life is worth living is just absurd.